Last night I was on Facebook and reading messages in one of the hydrocephalus support groups I subscribe to. The mom of a hydrocephalic child asked a question about ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) failure and constipation; being I have this blog, I started researching and found LOTS of articles, the only problem was you had to pay to view anything more than the abstract. Not to be deterred, I did another search this morning and found an article that presented enough information that I can intelligently respond to her question. To accomplish this, I am going to discuss the primary care needs of children with hydrocephalus and include the information about the VP shunt and constipation.

Clinical manifestations at the time of diagnosis

Although the signs and symptoms of hydrocephalus might be somewhat varied due to the specific cause of the condition, there are common clinical manifestations associated with the increased intracranial pressure (ICP) (See Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) at right). If the accumulation of excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) occurs slowly, the child may be asymptomatic until the hydrocephalus is quite advanced. Because of this, significant dilation of the ventricle(s) can occur before abnormal growth of the head is apparent. A myriad of symptoms including: 1) Full (or distended) fontanels; 2) Frontal bossing (protruding forehead); 3) Prominent veins in the scalp; 4) Vomiting; 5) Irritability; and 6) Opisthotonic posturing might be observed before dramatic changes are noted in head circumference.

| Roona Begum, age 5, was one of the more severe cases of hydrocephalus. |

In older children - where the cranial sutures have already fused - the development of hydrocephalus might result in the non-specific symptoms of headache, nausea, vomiting, and personality changes (including irritability or lethargy) might occur. In addition, spasticity or Ataxia (complete loss of control of a specific body part) or urinary incontinence can occur in more severe cases. The child might also experience vision problems such as extraocular muscular paresis (caused by increased pressure on the second, third, or sixth cranial nerves) and/or papilledema. If the increase in intracranial pressure occurs near the hypothalamus, alterations in growth, sexual development, or electrolyte imbalance may occur.

Associated problems

Constipation is not a secondary problem I would have associated with hydrocephalus, but turns out it is. To be completely accurate, it is not the problem per se, but, rather the elevated intraabdominal pressure which, in turn, places pressure on the distal end of the shunt (pictured at right) (Journal of Neurosurgery: Pediatrics, 2006). According to Constipation as a reversible cause of ventriculoperitoneal shunt failure there have been two (2) documented cases (including imaging evidence) of children with apparent VP shunt failure who were also severely constipated. Treatment of the constipation resulted in both clinical and imaging-documented resolution of the shunt failure.

Seizures occurring during infancy are not uncommon at the time of the initial diagnosis of hydrocephalus due to the increased intracranial pressure (ICP). An estimated twenty percent (20%) of infants with hydrocephalus continue to experience seizures after their first year of life. These seizures can be either simple or complex in nature (up until age eight, I suffered from absence seizures where my awareness and responsiveness were impaired) and are typically well-managed with standard anticonvulsant therapy. By contrast, seizures that occur with acquired hydrocephalus are more likely to result from the underlying cause (such as a brain tumor or infection) and are more difficult to treat.

The effects on intellectual function is difficult to determine early on in the disease process. The cause of the hydrocephalus seems to be the crucial point in determining how it - intelligence - will be affected. If the hydrocephalus is uncomplicated, it generally has a better prognosis than hydrocephalus resulting from a brain injury. In recent studies, two-thirds (2/3) of children diagnosed with hydrocephalus had normal or borderline normal intelligence (for reference purposes, 85 - 115 is considered normal). In children - with hydrocephalus - with an intelligence quotient (IQ) score above 70, their performance IQ scores are lower than full-scale and verbal IQ. This discrepancy indicates a need for both pre-school and school counseling and testing to identify areas of learning disability.

Visual abnormalities are often found either at the time of diagnosis or in the event of a shunt malfunction. The increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) result in optic nerve pressure, limited upward gaze (also known as Sunset sign or Parinaud's syndrome), extraocular muscle paresis, and Papilledema (shown at right).

Although their shunt is completely functional and their hydrocephalus is controlled, these children commonly suffer from vision problems such as strabismus (misalignment of the eyes), amblyopia (commonly known as "lazy eye" where the brain favors one eye over the other), nystagmus (rapid, uncontrollable movement of the eyes) or astigmatism (blurred vision resulting from an irregular surface contour of the cornea). Refractive and accommodation error is seen in between 25% - 30% of children with hydrocephalus.

Fine motor control is also affected by hydrocephalus. Kinesthetic-proprioceptive abilities of the hands are often affected negatively and, coupled with impaired bimanual manipulation and frequent visual deficits, make it difficult for a child with hydrocephalus to perform well on time-limited, non-verbal intelligence tests.

Primary care management

Growth and development

Both precocious and short stature have been documented in children with hydrocephalus. Sexual development prior to the age of eight (8) in girls and the age of ten (10) in boys is considered precocious and warrants additional diagnostic study. Height below the 5th percentile, if not compatible with family stature, is an indication of growth retardation. Treatment is available for both of these conditions and the child should be referred to an endocrinologist is symptoms of either condition persist.

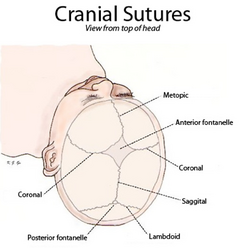

If a child is suspected of having hydrocephalus, their head circumference should be measured by an experienced medical professional. Until the cranial sutures (pictured at left) are completely fused - which can be delayed in a child with hydrocephalus - any increase of head size is a major indicator in diagnosing the child's condition. Once placement of a shunted has been completed, head circumference may decrease by one to two centimeters as the intracranial pressure (ICP) is relieved. Following this initial decrease, the child's head should grow in proportion to the child's body.

Standard infant developmental screening tools utilized in a primary care practice (such as the Denver Developmental Screening Tool) may be of little help when assessing an infant with hydrocephalus. It is important for the child's practitioner to interpret developmental findings in the context of clinical observations so as to assist the parent's in developing reasonable expectations for the infant. Some motor delays are to be expected during infancy and early childhood due to an estimated 75% of children with hydrocephalus having some form of motor disability. The primary care provider (PCP) should carefully document the acquisition of motor skills because the loss of these skills can be an indication of shunt malfunction or progression of the causation of the hydrocephalus. Additionally, ataxia, slurred speech, or a lack of progression in school can be an indicator of the deterioration of neurological status and a need for further evaluation.

Immunizations

Diphtheria, Tetanus, Pertussis (DPT) is an important immunization for a child with hydrocephalus because pertussis (commonly known as whooping cough) can cause a unique problem for the hydrocephalic patient. However, caution must be exercised due to the fact that infants with a history of seizures are at a higher risk of suffering a seizure after the vaccine is administered. For this reason, deferring this immunization until neurological stability is ascertained is advisable.

The measles vaccine has also been implicated in in post-vaccination seizures (in children with hydrocephalus) particularly if they have a previous history of convulsions. Seizures that occur post-vaccination are not believed to result in damage and, combined with the ongoing high risk of natural measles, justifies use of the vaccine even if the child has a previous history of seizures.

Haemophilus influenza type B (or HIB) is recommended for all children at eighteen (18) months of age. Due to an increased risk of HIB infection in a child with a shunt, they should definitely receive the vaccine as recommended.

For additional information: Primary care needs of children with hydrocephalus, VP shunts and constipation

References

Journal of Neurosurgery: pediatrics (2006). Constipation as a reversible cause of ventriculoperitoneal shunt failure. Retrieved on October 2, 2017 from thejns.org/

No comments:

Post a Comment