In part one of "Normal pressure hydrocephalus: the "grown-up" version of an under-recognized problem" we looked at what normal pressure hydrocephalus or NPH is and what symptoms are experienced. In part two, we will look at what causes it, how it is diagnosed, and what treatment options are available.

III. What causes normal pressure hydrocephalus?

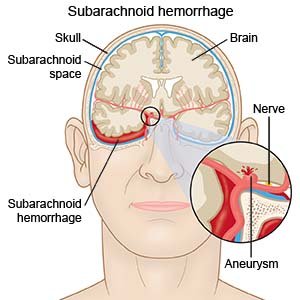

In the majority of normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) cases are classified as idiopathic meaning that it occurs spontaneously or that the exact cause is unknown. It should be noted, however, that there are known causes for NPH including: head injury, cranial surgery, subarachnoid hemorrhage, tumor, or cyst. Additionally, it can result from subdural hematoma, bleeding that occurs during surgery, or meningitis. It is interesting to note that all of the causes outlined above can predispose the patient to inflammation (which affect the cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] pathways) which impedes the CSF flow.

IV. How is NPH diagnosed?

In many cases, it is often the affected person or close family member who first brings the symptoms of NPH to the attention of a doctor. Additionally, there have been cases where the enlarged ventricles have been found on a brain image (such as a CT scan) that is performed for a totally different reason. If a physician has reason to suspect his/her patient has NPH, the doctor can order a variety of test to confirm this diagnosis.

Once NPH is suspected by the affected person's physician, it is imperative that a neurologist, neurosurgeon, or neuropsychologist be brought on board. Their involvement from the diagnosis stage onward is helpful not only from the standpoint of interpreting test results, but also in discussing the surgical option (if indicated), potential side effects and follow-up care.

As the diagnostic process moves forward, the decision to order a specific test might hinge on the given clinical situation. These might include, but are not limited to:

Clinical exam to evaluate symptoms consists of an interview (with the patient and their family) and/or a physical/neurological exam. (Hyperlink goes to a YouTube video.)

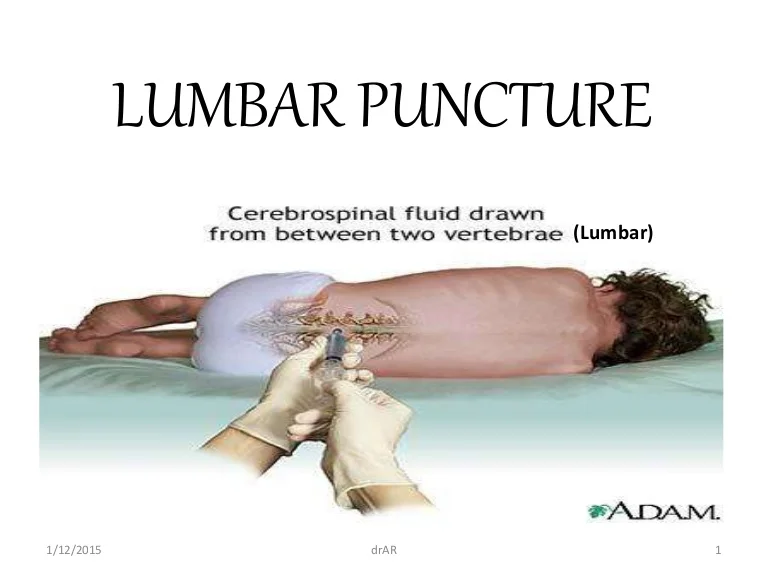

CSF tests to predict shunt responsiveness and/or determine shunt pressure include lumbar puncture ("spinal tap"), external lumbar drainage, measurement of CSF outflow resistance, intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring, and isotopic cisternography (pictured at left).

Lumbar puncture allows for an estimation of both the CSF pressure as well as analysis of the fluid. Performed under a local anesthetic, a thin needle is passed into the spinal fluid space of the lower back. The doctor then removes up to one (1) cubic centimeter (cc) of CSF are removed to see if a reduction in CSF volume relieves symptoms being experienced by the patient.

External lumbar drainage (also known as continuous lumbar drainage) is a variation of the lumbar puncture where a flexible catheter is left in place to facilitate drainage of the CSF. It allows for either continuous or intermittent drainage of CSF over several days to emulate the effect a shunt would have. It also allows for a more accurate reading of CSF pressure as opposed to the "moment in time" measurement provided by the lumbar puncture.

For intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring or spinal pressure monitoring a small pressure monitor is inserted through the skull into one of three places: 1) The brain itself; 2) The ventricles of the brain; or 3) The lumbar region to monitor ICP. It is utilized to detect an abnormal pattern of pressure waves as well as either low or high pressure. The results from this testing can be utilized to select an initial pressure setting if a shunt is being implanted.

Isotopic cisternography is no longer frequently used because a "positive" cisternography result does not reliably predict whether the patient will respond to implant of a shunt and the (cisternography) results are often ambiguous.

For additional information: NPH booklet

No comments:

Post a Comment